Facial Nerve Disorders

Whether it arises from injury, tumour, surgery or some other factor, facial nerve palsy has profound consequences for the patient. Everyday functions such as eating and blinking may be impaired, causing inconvenience and distress. The aesthetic and emotional effects of a paralysed facial nerve are often equally serious. Effective management of facial nerve palsy is best achieved through the co-ordinated approach of a multidisciplinary team of surgeons, physiologists and physiotherapists.

The facial nerve first began to interest anatomists in the 18th century. In 1821, Charles Bell demonstrated functions of the facial nerve. Bell’s palsy, the condition named after Charles Bell, is still quite controversial. The diagnosis of Bell’s palsy is made when an acute and one-sided facial weakness or paralysis occurs without an obvious cause. The facial paralysis typically occurs rapidly, and may be associated with pain or numbness affecting the ear, face or tongue. At present, the most likely underlying cause is believed to be a viral infection causing swelling and blockage of the blood supply to the facial nerve in the narrowest course in the ear bone. The diagnosis of Bell’s palsy is made when other causes such as trauma, tumours, infection and developmental abnormalities are excluded.

Facial Nerve Surgery

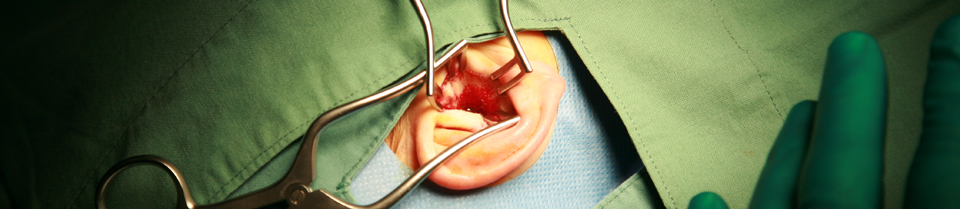

The facial nerve takes a curving course through the ear bone and into the parotid gland to supply the muscles of the face. The most common cause of facial paralysis requiring surgery is trauma which results in damage to this nerve. Traumatic events affecting the facial nerve may occur as a result of motor vehicle accidents, direct blows to the head and, unfortunately, surgery. The nerve may be cut or bruised by any form of trauma. On some occasions, patients develop facial nerve paralysis from damage to the facial nerve which has occurred years before. Such damage may require complicated and intricate microsurgery to restore facial nerve function.

Special surgery on the facial nerve using microscopic techniques allows the surgeon to either reduce the pressure on the nerve or insert nerve grafts.

Tumours of the Facial Nerve

Benign tumours affecting the facial nerve are rare but are an important cause of progressive facial nerve paralysis. The tumours are generally benign and are called facial neuromas. The facial nerve neuroma is usually removed and the nerve reconnected with grafts.

Eye Problems and Facial Paralysis

The eye is commonly affected by facial nerve paralysis because the surrounding muscles are unable to close the eye properly. Facial paralysis is often associated with a lack of tears and inadequate lubrication. This dryness and incomplete closure of the eye, may lead to permanent damage to the eye surface.

Surgery can be performed on the eye to allow better closure and protection from dryness and damage.

Long Term Management of Facial Paralysis

There are many techniques available to provide improvements in function of the facial nerve. Operations designed to reconnect the facial nerve to other nerves may lead to vast improvements in facial movement and appearance. Muscle grafts, facelifts, browlifts and eye surgery can all be combined to help the patient with a long term facial paralysis.

Facial Nerve Physiotherapy

Facial nerve physiotherapy has a vital and practical role to play following surgical treatment and in the long-term management of acute facial paralysis. Newer techniques using injections of botulinum toxin also are useful in the prevention of muscle spasm that may occur after facial nerve injuries.

Facial Nerve Disorders – The Team Approach

Specialised teams comprised of ear surgeons, eye surgeons, plastic surgeons, electrophysiologists and facial nerve physiotherapists at St Vincent’s Hospital have an extensive and impressive record in the management of facial nerve paralysis. Members of the team have published widely in the international literature and the results of surgery have improved the lives of many patients with facial paralysis.

Selected Publications:

Fagan PA, Loh KK: (1989) “Results of Surgery to the Damaged Facial Nerve”, J Laryngol Otol. 103: 567-571

Fagan PA, (1989) “The Assessment and Treatment of Facial Paralysis” Aust Fam Phys, 18: 1400-1419.

Fagan PA, (1990) “Progressive Facial Palsy due to Fibrosis” Am J Otol. 11: 459.

Buchanan D, Fagan PA , Turner JJ (1991), “Facial Schwannoma: A Case of Unusual Endoneural Spread” J Otolaryngo Soc Austral. 6: 523-525.

Watts A Fagan PA, (1992) “The Bony Crescent Sign – A New Sign of Facial Nerve Schwannoma” Aust Radiol. 36: 4; 305-307.

Fagan PA, Misra SN, Doust DB: (1993) “Facial Neuroma of the Cerebello-Pontine Angle and Internal Auditory Canal” Laryngoscope 103: 442-446.

Robertson DW Turner J Fagan PA (1994) “Extensive Facial Nerve Tumour with Atypical Histology: A Case Report” Am J Otol. 15: 437-440.

Behera SK, Misra S, Fagan PA (1994) “Facial Nerve Neuroma: Diagnosis and Management” Indian J of Otolaryngol H & N Surg. 3: 6-10.

Fenton JE, Fagan PA, (1995) “Iatrogenic facial Nerve Injury” Laryngoscope 105: 444.

Liu R, Fagan PA, (2001) “Facial Nerve Schwannoma: Surgical Excision Versus Conservative Management” Annals Otol Rhinol Laryngol 110:11 1025-1029

Fenton JE, Chin RYK, Tonkin JP, Fagan PA (2001) ‘”‘Transtemporal facial nerve schwannoma without facial paralysis” J Laryngol and Otol 115 559-560

Wijetunga R, Doust B, Roche J, Fagan PA, “Facial nerve tumours” – Poster presentation, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists, 54th Annual Scientific Meeting, Brisbane, October, 2003.

See also St Vincent's Ear, Acoustic Neuroma, and Skullbase Courses for clinicians.